Architecture in pandemics

May 03, 2020

by Ignacio Alonso

'People don't know how to imagine the future, and they tend to repeat the past when they try' Eduardo Punset (1936-2019) IMF economist and science divulgator

In the recent history, pandemics and infectious diseases have certainly affected the humankind, mostly those living in urban environments. Architecture has almost always responded in a way, either resulting in code and regulation changes, new typologies, new types of urbanism, or even new forms of use. In this article we will go through some of the architectural responses during the recent past, and find out how they changed the forms of living, from the individual scale (housing unit) to the global scale (city) and introduce some of the current options to form a better future.

Historical vision: infectious diseases (1850 to 1915)

Diseases caused by infections hit hard most urban environments during the end of XIX and beginning of XX century, mainly as a consequence of the rapid increase of the urban population without an adequate improvement in the healthy living conditions. In 1900 and just in the United States of America, these types of diseases represented the 3 primary causes of mortality (Pneumonia, Tuberculosis, and Gastrointestinal infections), putting life expectancy at 47 years (1).

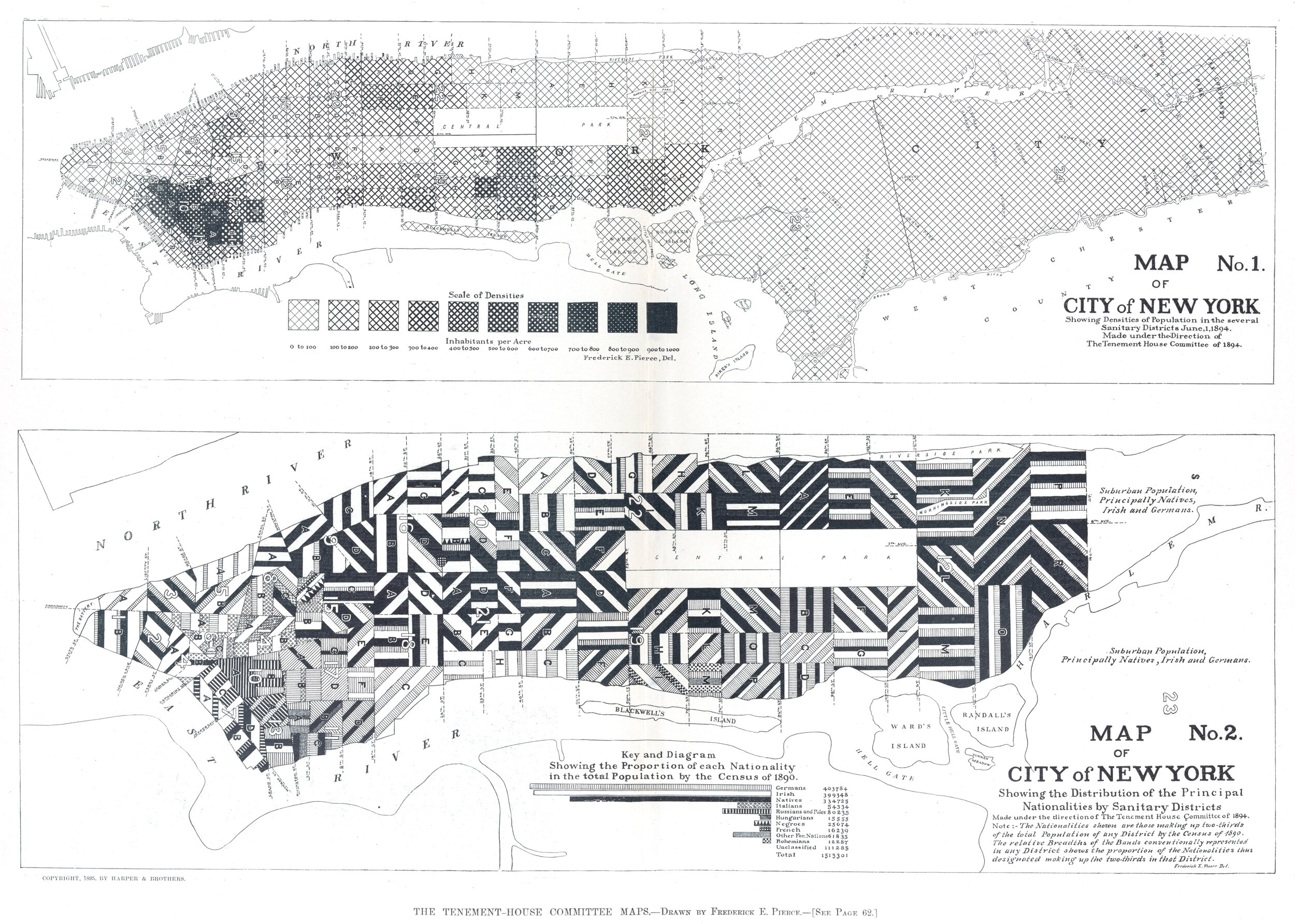

In the specific case of the City of New York, in 1894 some areas of the Lower East Side had population densities beyond 900 hab per acre (2) (225,000 hab per km2) - see Fig.1 ; currently Manhattan has an average of 25,800 hab per km2. Just understanding this data makes it easy to imagine some of the population's confinement at that time.

In 1903 the vast majority of the housing for poor people only had shared water closets installed in common hallways, without privacy, and some installed at the rear yards. Only in New York City there were about 82,000 constructions of this type (3) , and up to 79 families were forced to use a same bath tub (4).

One of the first voices to raise alarm about these conditions was Dr. Simon Baruch (1840-1921). He established his practice in New York City in 1881. Dr. Baruch became an advocate for the use of fresh water to avoid and cure infections. His book 'Principles of Hydrotherapy' (1898) is probably the best expression on that direction. Thanks to his studies and efforts he persuaded the Governor to make immediate changes: the Public Baths were born.

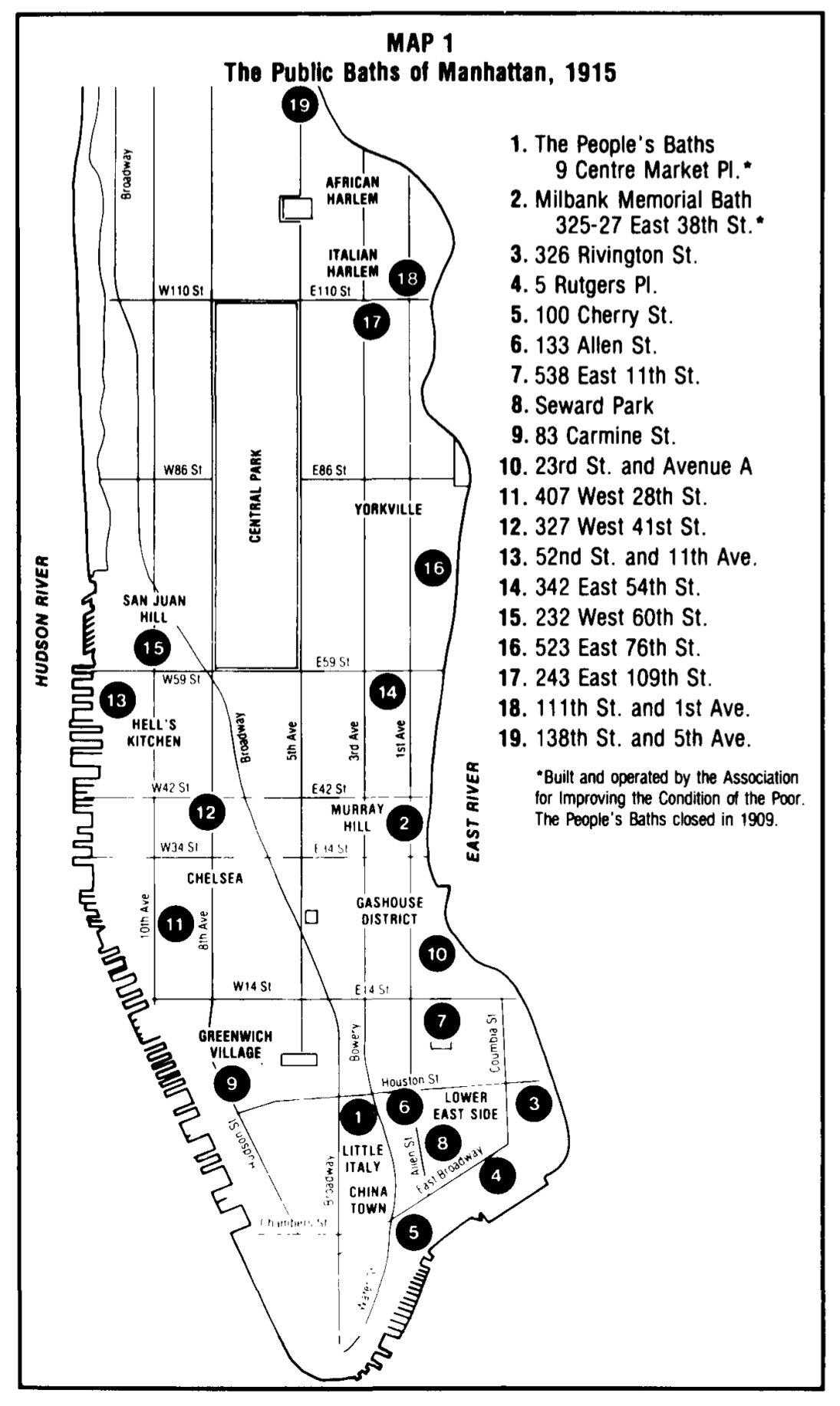

In 1895 the State of New York passed the law for erecting Public Baths in all urban settlements beyond 50,000 people. In 1897 a first Public Bath in Manhattan was open (9, Center Market Place). Only in New York City up to 18 public baths were erected - see Fig.2.

The rebirth of Public Baths can only be attributed to legislative's slow pace to implement individual bathing inside dwellings and its technical difficulty, and as an emergency solution to resolve immediately the problem at a city scale.

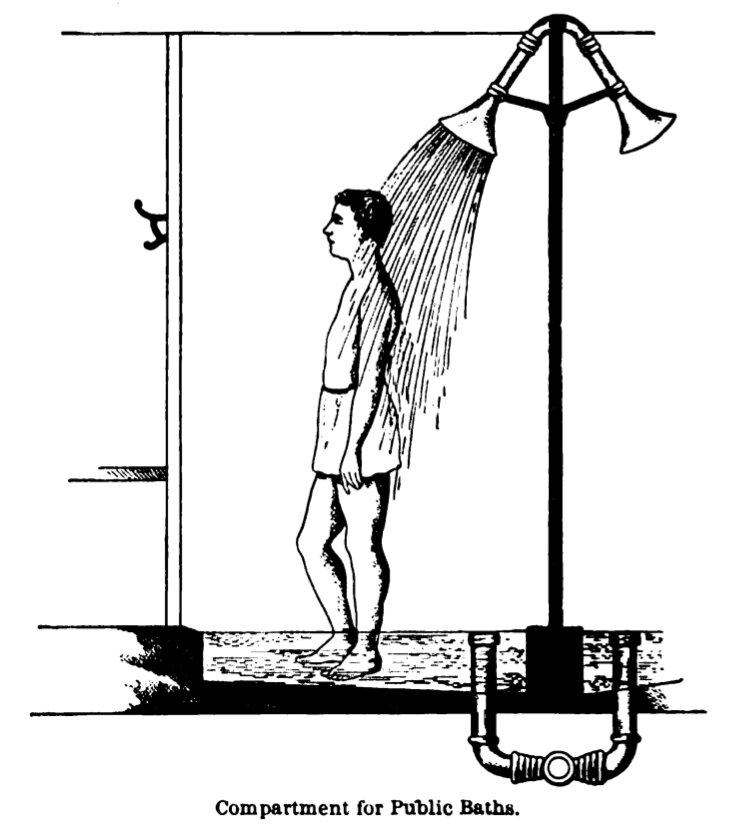

The construction of the Public Baths was founded with public resources and focused on personal hygiene, unlike other similar constructions more focused on the lucrative side like the Turkish Baths. Their establishment will allow technological development on systems that shortly after will be key in disease control and prevention, like personal shower - see Fig.3.

As a consequence of the Public Baths establishment, a new culture of hygiene was born, which resulted after time in a demanding matter from the population. In 1901 a new tenement law was passed including mandatory bathrooms in residential dwellings. Thanks to the persistence of new technology development to reduce construction cost, in 1916 one piece amanel galvanized tub was invented.

Already in 1934 and during the Great Depression, a survey in the City of New York only found 11% of dwellings without private bath tub or shower.

A bright future: flexible spaces

The greatest years in boom construction in the City of New York were between 1900-1930 (5). This period of construction represents today 63% of the city's total residential buildings, which means that the surviving buildings are in average 90 years old. The situation is pretty much the same in most of historical European cities.

Therefore seems logical to consider an average longevity rate for the planning of any new construction and/or rehab. It's almost impossible to predict what will happen in such a large span of time and how a building will be utilized during the entire period, but current technology and construction methods can easily help to set a up a strategy to facilitate any future change of use of any given new or rehab structure, so use changes can be accommodated in an easily manner.

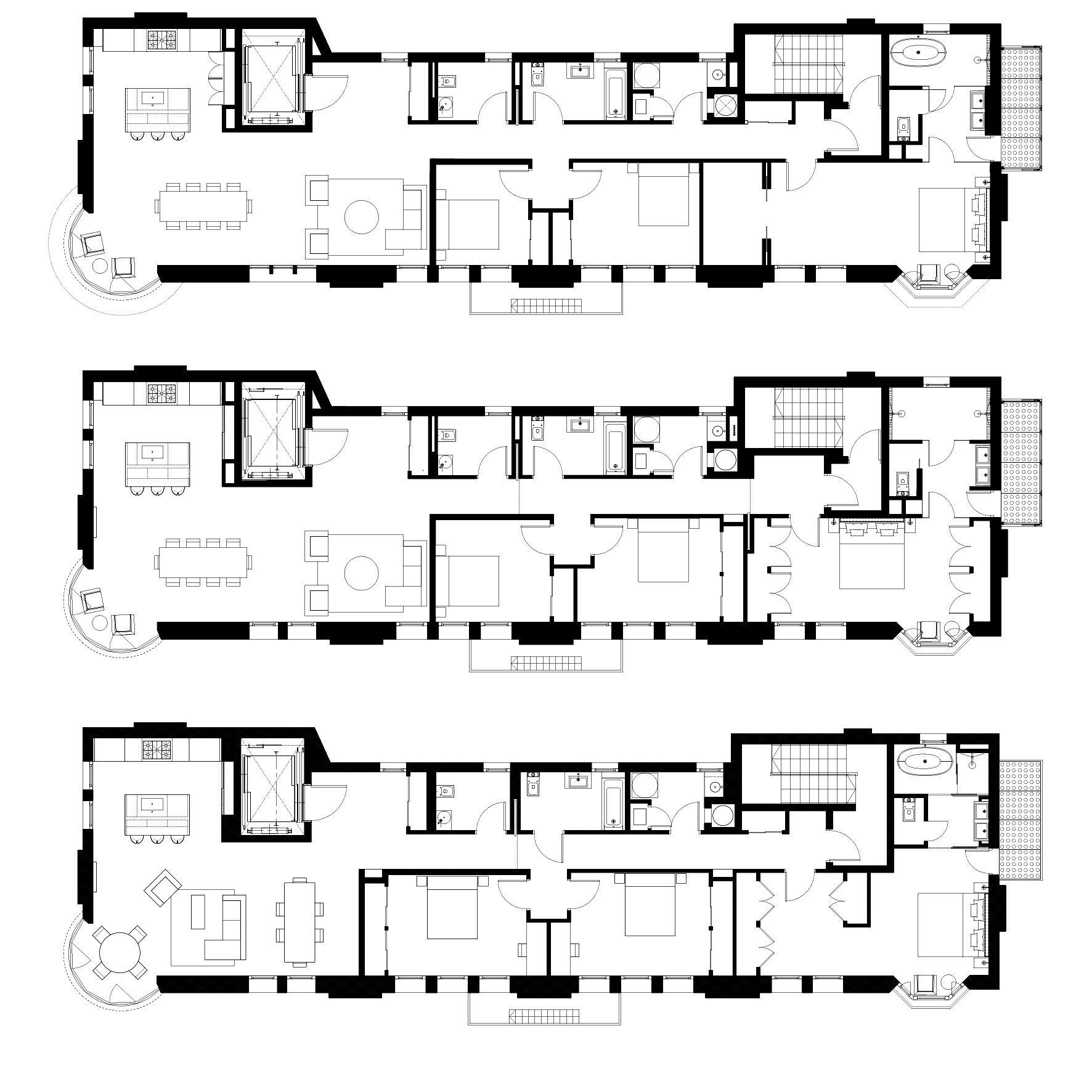

The 187 7th Avenue building (Park Slope, Brooklyn, erected 1920) was object of a full rehab in 2016 - see Fig.4. Located on a corner lot, its footprint occupies almost 100% of the space, resulting in a 25' x 90' rectangle. Each floor is occupied with a single apartment, with direct access via stairs and elevator.

The goal of the design was to create a new residential type that allows interior layout changes through time and being easily adaptable to each owner personal requirements - see Fig.5.

With this in mind, all wet areas (such as bathrooms, kitchen and wet room) and cores (stairs and elevator) are arranged in a single strip. This set up eases the rest of the interior space of any vertical penetration (such as risers, shafts, etc.) and allows complete freedom for the interior partitions layout. The finished floor (American oak) was installed continuously throughout making the interior walls floating above it, so when they get changed there are no traces of what was there before - see Fig.6. The heating system is a Hydronic radiant floor system installed in the same way, so heat is always equally distributed no matter which layout there is.

With this set up any changes on the layout can be accommodated in an easy manner using dry construction and avoiding a need of any other trade such as plumbing or electrical, and without affecting any service for the rest of the building.

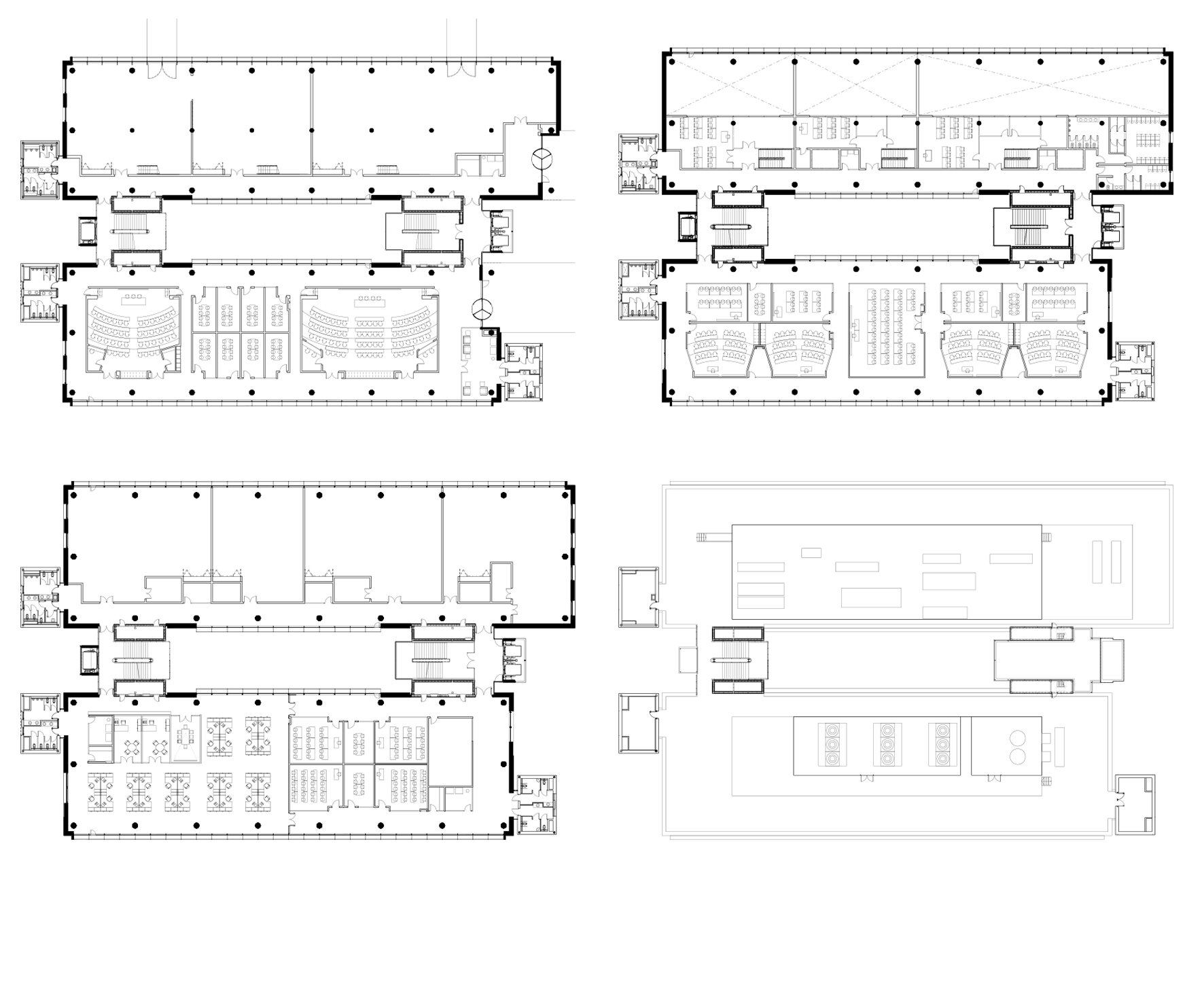

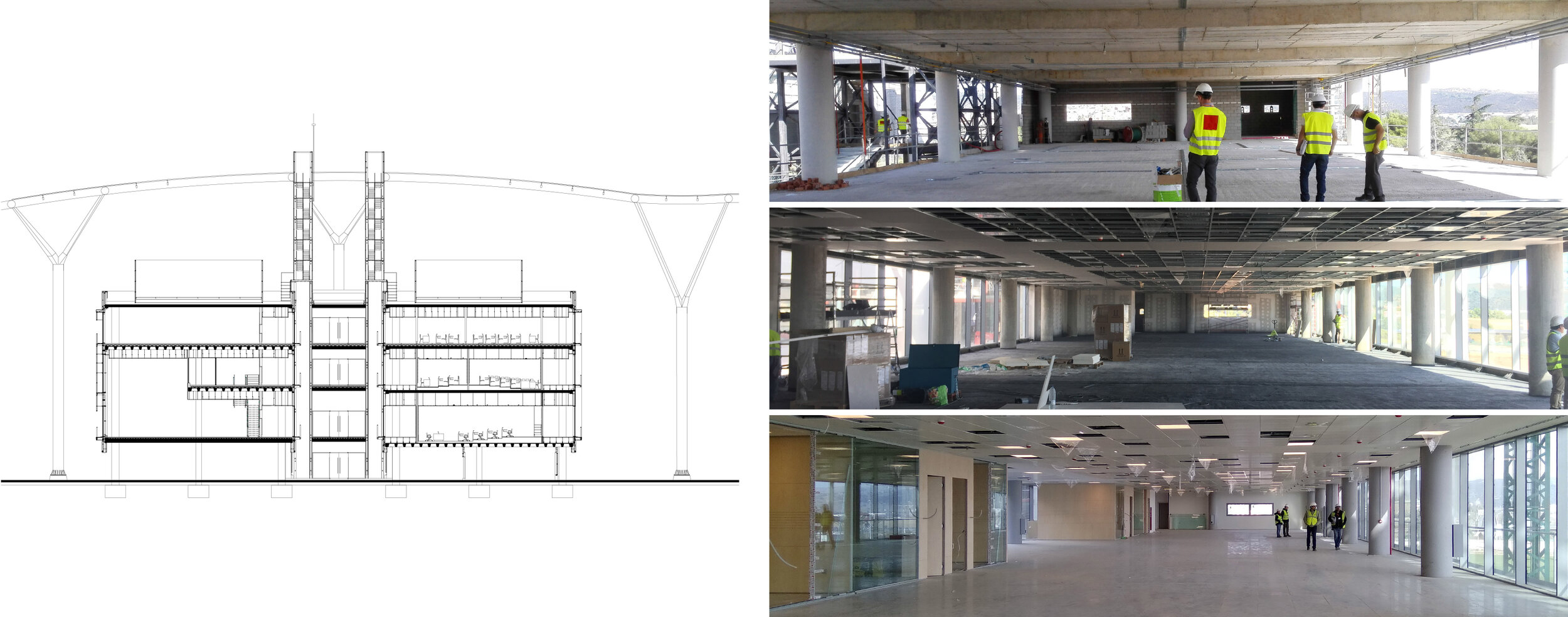

Not only residential housing can be subject to layout adjustments as a result of working remotely, kids leaving to college, reuniting grandparents at home or expanding storage area; educational uses are also subject of layout changes mainly due to continuous introduction of new technologies. Most probably it is educational uses that will require larger functional variation in time. Keeping the concerns of the future of education in mind, the Iberdrola's Corporate Campus was designed - see Fig.7.

Iberdrola's Corporate Campus consists of seven ground-up buildings. All buildings have exterior cores (stairs and lifts) and exterior risers (mechanical, electrical and plumbing) - see Fig.8 and Fig.9; in four of these buildings the wet areas (bathrooms) are also exterior - see Fig.10. By the use of big spans - up to 16m- the buildings can achieve up to 1,000 m2 'empty' floor plates without a single vertical penetration - see Fig.11. This strategy allows great modularity for the internal spaces, and a total flexibility in the interior layouts, so the spaces can be reconfigured after time without any restriction.

No crystal ball is available to predict what the future will hold, but there're available strategies that can facilitate facing any kind of future.

Source:

(1) Carolina Demography, data source by Centers for Disease Control

(2) New York State Tenement House Committee 1894, source: Wikipedia

(3) Tenement House Problem, Macmillan & Co. Ltd 1903

(4) What became of New York's ubiquitous Public Bathhouses?, source: Curbed New York

(5) PLUTO built-year data, source: NYC Department of Buildings